Ciudad de México

In the heart of Mexico

(Part I)

Instead of a PROLOGUE

What comes into our minds when we hear the word Mexico? Stereotypes or reality? Mexico is the Aztecs and the mysterious Mayan temples hidden in the jungle, Acapulco, and the vast white sand beaches of the Yucatan Peninsula. Mexico is the ranchero songs, the mariachi, and Chavela Vargas; it is Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; it is cacti and Mexicans taking their siesta wearing ponchos and sombreros. Mexico is color, tamales, tacos, enchiladas, burritos, chili, tequila and mezcal.

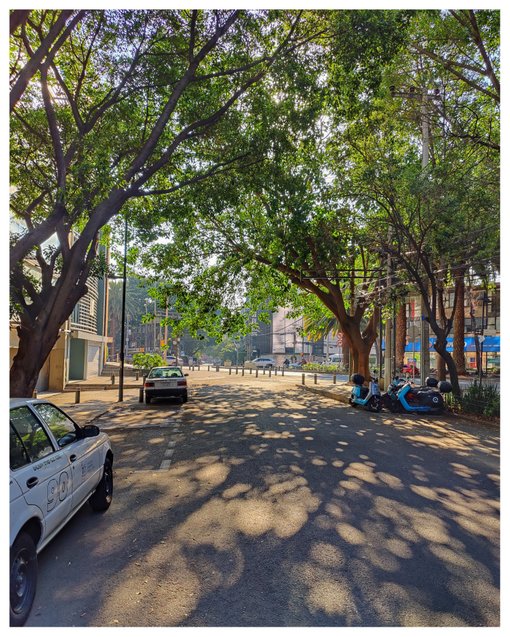

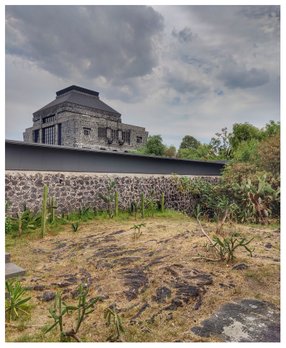

Typical mid-war house in the center of Mexico City (zona rosa).

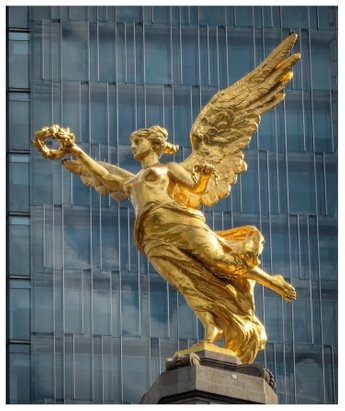

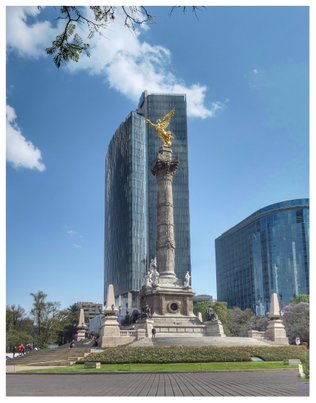

But what about Mexico City? Besides the landmark of the golden statue of Angel, I had no idea what this megapolis looked like. I recently acquired an image of Mexico City from Alfonso Cuarón's Oscar-winning film 'Roma', a black and white image from the 70s. Surprisingly enough, it does look almost the same! But, I don't know what I expected to see in Mexico City when planning my trip to the distant Central American country. I liked what I saw but didn't think the city would look like this today.

First Impressions

After a long and tiring journey, I landed at Benito Juarez international airport in Mexico City. The taxi I had ordered online was waiting for me, and we started the 30-minute journey to our hotel in the Roma Norte area, yes, that "Roma" from the movie.

I could not figure out precisely what other city this one reminded me of as we drove through it. It probably reminded me more of Southeast Asia and maybe a bit of Buenos Aires. But still, it was something I had never seen before. From the first moment, what surprised me was the intense vegetation of the city, the thousands of electric and telecommunication cables that hung from poles above the streets, forming an almost impenetrable curtain, and the low buildings of another era that, yes, were precise, as in Cuarón's memory. Accustomed to Athens, where almost all the buildings of the early 20th century and the end of the 19th century have been replaced by apartment buildings of very low aesthetics, I was rather shocked to see the preserved architectural wealth of the city.

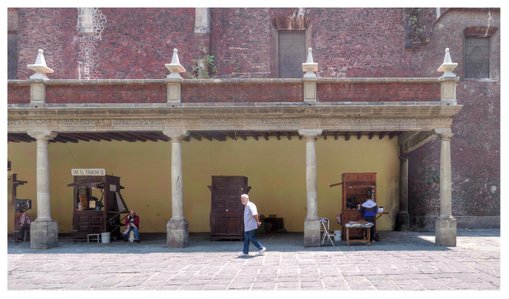

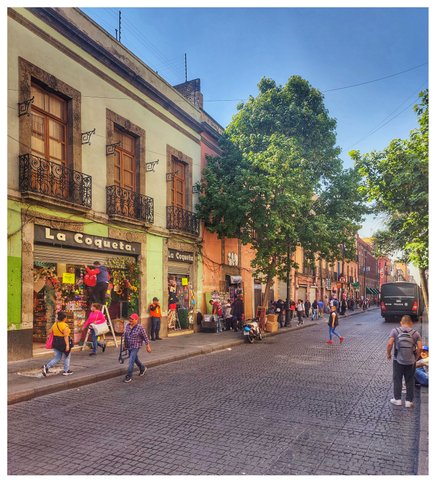

Street vendors in central Mexico City.

People native to Mexico City are called "Chilango" or "Chilanga" when referred to a female.

A famous phrase used by people outside Mexico City that says: "Haz patria, mata a un chilango," which means "Be patriotic, kill a chilango", is not intended to be used literally but with a mocking tone. The phrase, coined in the state of Sonora, reflects an attitude typical in many states of the nation of disdain and rivalry against residents of Mexico City that peaked in the 1980s. Then, in response to this phrase, Chilangos began to add, "Haz patria, educa a un provinciano", which means "Be patriotic, educate a rural person". People in Mexico City refer to people from the rest of the nation as "provinciano(a)". "Chilango pride" has also led to the term "Chilangolandia" referring to Mexico City.

A couple of days later...

Mexico City is a big city which is stressful in itself. In the first days, it is difficult to get used to it, and you also have to be hysterically careful with drinking water and eating fruits and vegetables because dysentery is waiting for you around the corner. Combine that with jet lag, the high altitude the city is built at, environmental pollution, and the potential heat, and you have the perfect cocktail of misery.

Should I not come at all? Should I have avoided the 20-hour plane ride at my age? Should I reconsider before it's too late and take the first plane back home? Lots of "should"! But what on earth am I talking about? It was a lifelong dream to visit Mexico! And here I am—no more moaning.

After a few days, none of the above makes sense, and you feel at home or almost at home. I never passed the difficulty breathing or coping with air pollution. But, soon, I forgot all the stories about the criminals in this country who hide behind every ATM and every dark corner and are eager to rob, stab, or even kidnap you. My 85-year-old mother told me this when I told her I was going to Mexico.

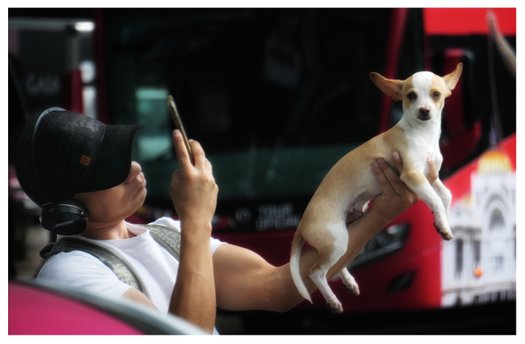

Mexicans are very dangerous, they even shoot chihuahuas!

Remember: you will never regret paying extra money and staying in a good neighborhood, such as Roma Norte, Roma, or La Condesa. These neighborhoods are very welcoming, gorgeous, and secure. Also please find a reasonably good hotel, because after coming back to your room exhausted, having walked kilometers in the noisy city, you need a good bed, bathroom and probably a filter installed to your water tap to wash your food safely. I chose to stay in Roma Norte for my three-week stay in Mexico City. My choice of hotel was such that I felt perfect the moment I entered my room.

Roma is a 2018 drama film written and directed by Alfonso Cuarón, who also produced, shot, and co-edited it. Set in 1970 and 1971, Roma follows the life of a live-in indigenous (Mixteco) housekeeper of an upper-middle-class Mexican family as a semi-autobiographical take on Cuarón's upbringing in the Colonia Roma neighborhood of Mexico City.

The house at 22, Tepeji street (Roma Sur), where Cuarón's film shot.

Moving around in the city

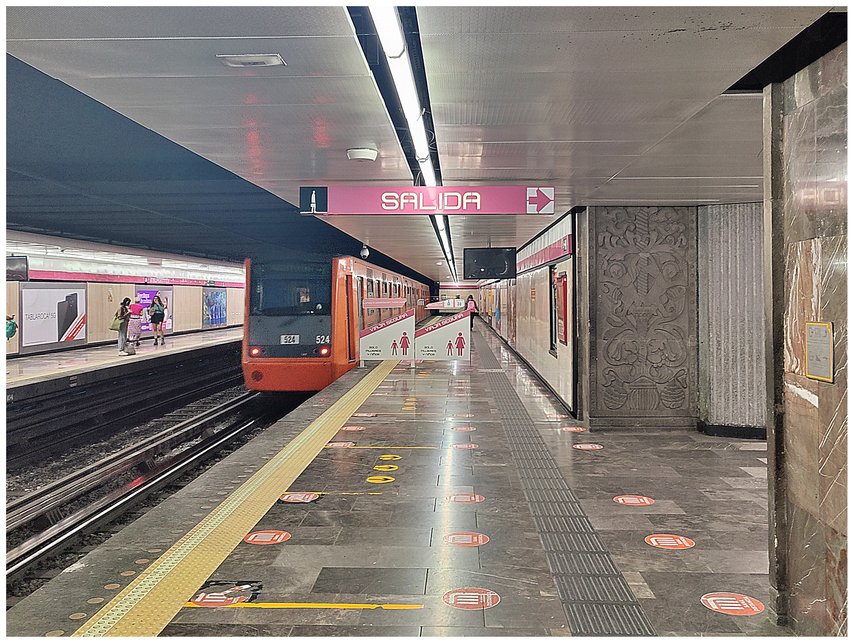

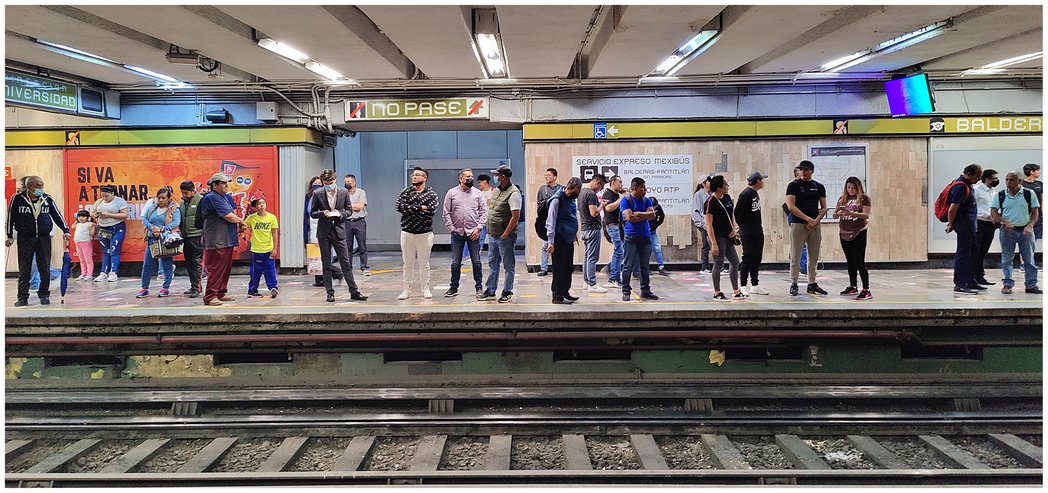

Mexico City is significantly populated, and the traffic can be a nightmare. The most accessible and useful for tourists are the metro, which has an impressive network, and the Metrobus. Its excellent public transportation system includes the metro, Metrobus (buses that run in dedicated lanes on major arteries and have metro-like stops), trolleys, buses, and cable cars. You definitely won't be using the cable car, which has been deployed in the run-down areas around the city, as a quick means of people moving to the city faster. A single card (tarjeta) can be used for all means of transport. You fill the tarjeta with as much money as you want, and after that, the price of each journey is deducted by placing it on devices entering the station or on the bus. The price for a single ride (transfers are allowed) is meager, mainly because the state subsidizes it.

The metro stations have sections (at the platform's beginning or end) specially dedicated to women and children under 12. These are in use during rush hours for security reasons. All metro stations are staffed by police officers, which makes you feel secure.

You can forget all of the above and use Uber. For long distances, where, if using the metro or bus, I should need to transfer from one stop to another, I only used Uber. Besides being the safest transportation method in the City, Uber is inexpensive and practical. I remember one day I was riding a Uber car, and at some point, we were stuck at the traffic lights for about 3 minutes, and immediately I received a message from my Uber App asking me if everything was OK or if I should press the "alarm" for help!

Of course, there are taxis, but they are more expensive than Uber and not that safe (unless you know what you are doing). One interesting point about taxis is that they are painted pink and white. At some point, the City painted the taxis with these colors to

raise awareness about breast cancer.

Mexico City "tarjeta".

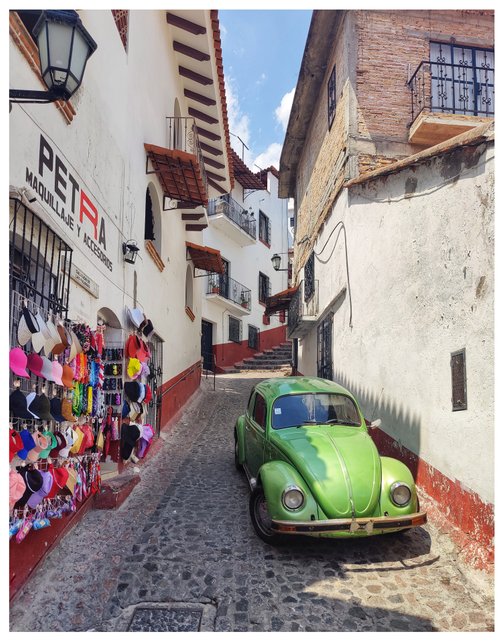

In the city of Taxco, most taxis are old VW beetle cars.

The pink-white taxis of Mexico City.

During rush hours, there are sections in Metro Stations for use by women and children only.

In metro and Metrobus systems, stations, in addition to their name in Spanish, also have a symbol-image (pictograph), which is unique to the particular station.

When Work began in 1967, Mexico City’s metro system signified a dramatic modernization of the cityscape. Making room for the metro meant clearing away some familiar aspects of the urban landscape and introducing residents to the strange new spaces of the network’s underground tunnels and stations.

To integrate this new layer of urban infrastructure with the existing city’s pre-Columbian, colonial, and contemporary layers, the authors of the subway relied on a pictographic system. A New York-based graphic designer, Lance Wyman, designed icons to identify each metro station.

Instead of a name, this new geographic entity was visually connected to an existing historical or geographical feature. Thus, the sign for Balderas station, where Line 1 met Line 3 in the historic center, referenced a cannon on display in a library above ground. In contrast, nearby Pino Suarez station was identified by the Aztec ruin uncovered (and destroyed) during excavations for the station.

Wyman’s visual system connected the surface to the underground. He created a visible match between the tight spaces of the city, which were now connected to the new stations via street signs, and the far more abstract underground space of the metro system.

In the dark tunnel, each pictograph would help the traveler to connect his or her location to familiar references above ground. With Mexico City’s modernization still a work in progress, the visual system also negotiated the fact that many of the system’s new passengers could not read.

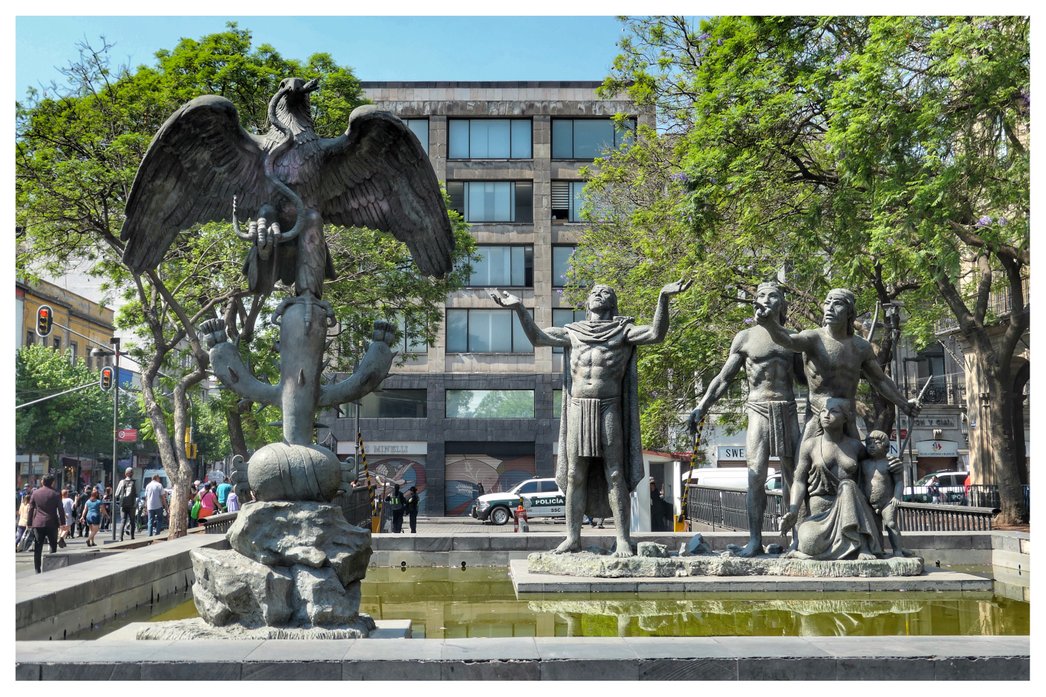

A story about an Eagle, a snake, a lake and a City

Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, was founded by the Aztec or Mexica people around 1325 C.E., where today's Mexico City is built. According to legend, the Mexica founded Tenochtitlan after leaving their homeland of Aztlan at the direction of their god, Huitzilopochtli. Huitzilopochtli directed them to build, where they saw an eagle perched on a nopal cactus (prickly pear cactus), eating a snake. When they saw this scene on an island (located in what was once Lake Texcoco), they interpreted it as a sign from their god and founded Tenochtitlan on that island.

The eagle and cactus have long been symbols of the Aztecs, a highly advanced Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in modern-day Mexico. Representing the Aztecs' tenacity and resilience, the eagle and cactus were two of the most prominent symbols of the Aztec Empire. The eagle was not only a symbol of strength and freedom, but it was also associated with the god Huitzilopochtli, the Aztecs' patron deity. Meanwhile, the cactus served as a spiritual and practical symbol of survival in the harsh desert environment.

The eagle eating a snake on a cactus is the official Coat of Arms of Mexico and appears on the country's flag.

The monument in Mexico City Zócalo shows the moment the Mexicas faced the eagle on the site where they would build their new capital.

Some little Mexican Things

Air Pollution

Mexico City is situated in a valley surrounded by mountains on three sides. The city is situated at 2,240 meters above sea level. Because there's less oxygen at this altitude, most air pollution results from the incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons, mainly diesel emissions. In 1992, the United Nations named Mexico City " the most polluted city on the planet" and "the most dangerous city for children" six years later. Since then, things have improved, or so they say. I live in a polluted city, Athens, so one should say that I am used to living in such an environment. Wrong! For the first moment, the pollution in Mexico City miscued me. I had problems with my throat, my nose was always dry, and my eyes stung. All these symptoms insisted all three weeks I was there. One could say that I did not get used to it.

Air pollution makes the sky hazy, and most of the time, one cannot see the mountains on the horizon.

The low-hanging wires

One of the things that negatively impresses the visitor in Mexico City (but also in the rest of Mexico) is the electric and telephone cables that hang between houses and poles over streets and sidewalks. All cables are exterior and not underground like, for example, in Europe. The problem is that there are so many of them that they often hide the beautiful facades of the buildings. Cables are also above the ground in other parts of the world, such as North America and Japan. But they are more or less tidy there, although they still make a lousy impression. Here in Mexico City, when a cable is no longer used or cut, it is not removed; it just co-exists with the new cables. When an electrical link fails, it is overlooked, and a new one is installed. The cut or loose wires often reach very low above the sidewalks where people walk, making you wonder how safe this is. The truth is that a similar situation exists almost throughout Latin America.

Of course, you get used to this situation after a few days, and it seems "normal".

Low-hanging wires in a very central street.

Greenery

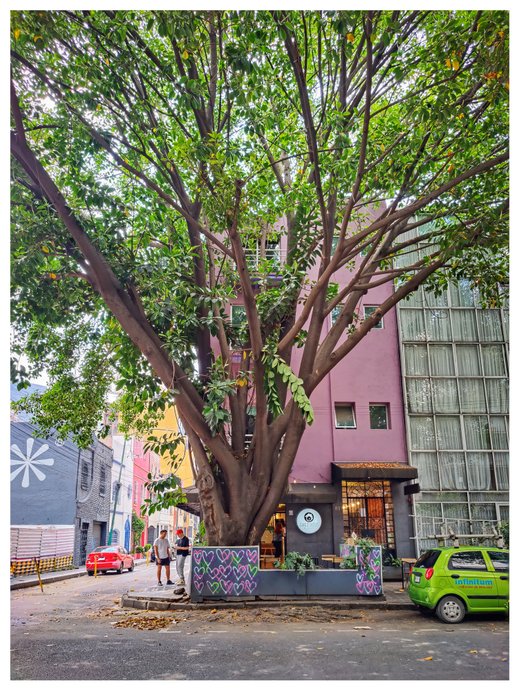

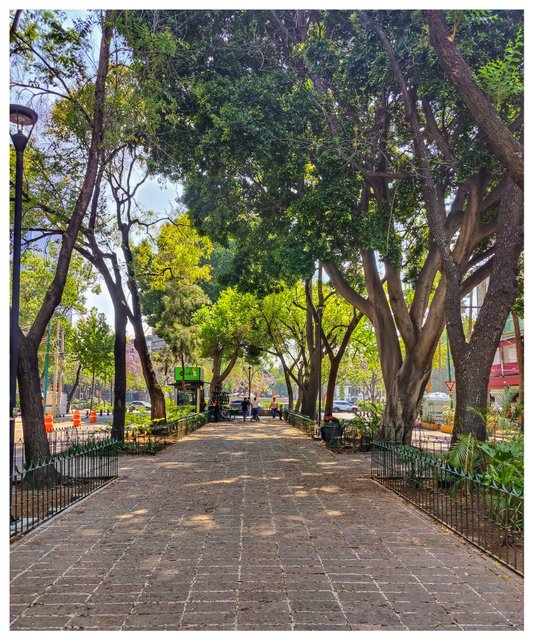

One thing that positively impresses the visitor to Mexico City is its many giant trees on its streets. This mainly concerns 'good neighborhoods' and, to a lesser extent, slums. In most parts of the city, the trees are so tall that they form shady arches or canopies over the streets, relieving citizens during hot summers. Some trees, mainly rubber trees (Ficus elastica) and Ficus trees (Ficus benjamin), are so big that their roots destroy the sidewalks around their trunk.

Other relatively common trees in the city are the Blue Jacaranda, the Mexican Sycamore (Platanus Mexicana), the Ear Pod Tree, the Brazilian Pepper Tree, the Wild Papaya, and the Ahueheuete.

However, it is not only the trees that impress, but also the planters that exist on the sidewalks, the small gardens in every corner of the city, and the large parks which look perfect from a horticultural point of view. It's evident that Mexicans love plants and flowers, and they are eager to show them. Everywhere in the city, you see gardeners tending to the plants and watering them.

A huge rubber tree.

In many parts of the city, there are small gardens with cacti, the plant symbol of Mexico; two of the most beautiful ones are in the "Jardín Botánico del Bosque de Chapultepec" and on the "Plaza del Marqués" outside the "Catedral Metropolitana".

Huge rubber tree roots exposed on a pavement.

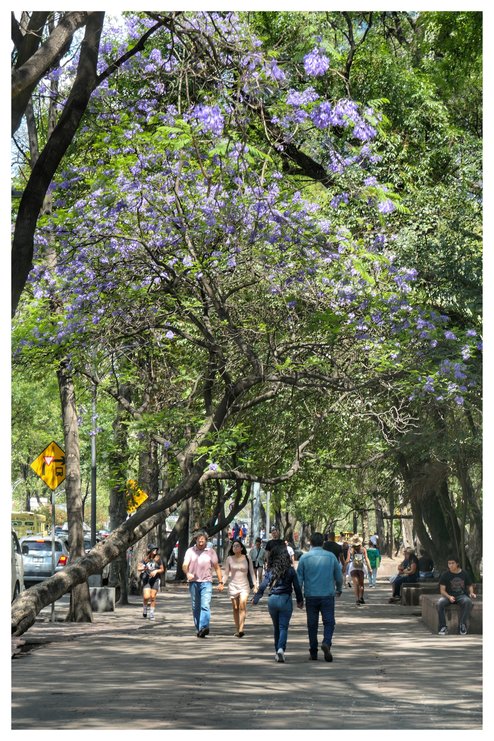

Jacaranda blossomed trees.

Jacaranda trees

The best time to visit Mexico City is in Spring! The cold winter mornings have passed, yet the summer's heat is always off. And best of all, Spring brings the beautiful violet petals of the Jacaranda trees into full bloom. The city becomes awash in its purple flowers, seen below and above. When flying into Mexico City in the Spring, keep your eyes peeled as you descend. You'll be amazed that the purple trees can be easily seen from the air above.

I was awestruck the first time I walked outside my hotel to see these beauties in real life. After arriving in the darkness of the evening, the morning light greeted me with an explosion of color. The Jacaranda trees in Mexico City, with their pale periwinkle and violet blossoms, are a valid symbol of primavera. Jacaranda trees are in full bloom from mid-March to April. And they're at their best in the latter part of that period. So, I was there at the right time!

Typical Roma Norte roads.

Lost in translation

You would think that Mexico's proximity to the US and the large number of American tourists visiting Mexico City would result in most people speaking at least some basic English. Alas! It's so hard to communicate if you don't know Spanish. Even in Japan, I could communicate better in English than in Mexico! Of course, it's good to know some basic Spanish because the locals appreciate the effort, but it probably wouldn't help you much.

Museums and galleries

Mexico City has to be the city with the most museums and art galleries in the world. No building block in the city does not have a museum: it is logical for a country with such a great, ancient, and modern culture. Most visitors limit their visits to prominent museums, but the small ones make the difference. All the museums and galleries I visited were beautifully laid out and interesting. However, if you only have to visit 2 museums, these must be the excellent 'Museo Nacional de Antropología' and the masterpiece 'Museo de Arte Popular'. Both will introduce you to the magical world of this incredible country.

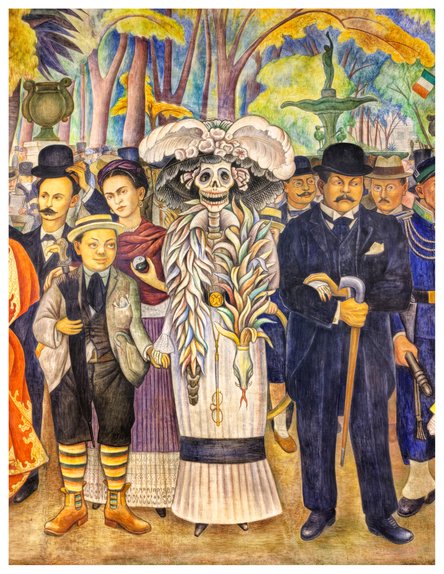

Diego Rivera's 1947 mural "Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central" in Museo Mural Diego Rivera.

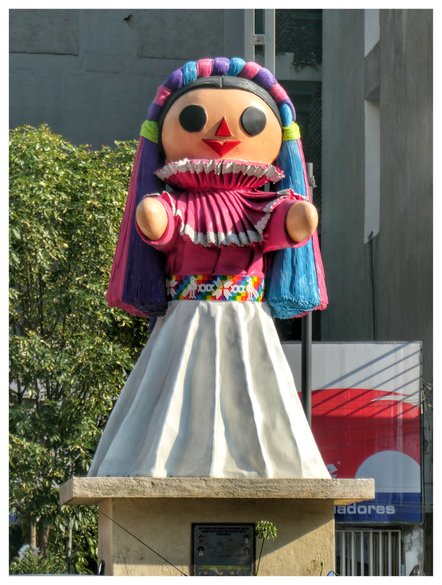

The origin of Lele arises from a fusion of pre-Hispanic rites with Spanish customs. Although they are currently made of rags and colored ribbons, it is believed that the first was made with clay, palm, and corn hair. Tradition has it that these dolls were placed in children's graves to ward off the evil spirits of deceased children. With the arrival of the Spaniards, they served in the markets as a perfect alternative to toys imported from Spain, mainly porcelain dolls.

About 10 thousand Otomi artisans from the communities of Santiago Mexquititlán and San Idelfonso Tultepec, both in the municipality of Amealco, organized themselves in a cooperative and put a lot of effort and work into their project to create Lele and make the doll so widespread. Thanks to social networks, the dolls went viral in a few years, and their sales increased and became so popular that today it is considered one of Mexico's symbols.

Monumento Lele on Chapultepec Avenue, in Mexico city.

Muneca Lele bought as a souvenir.

Muñeca Lele

Just as tacos, tequila, and mariachis are symbols of Mexico, the Lele doll became the icon of Querétaro, which the world fell in love with.

Lele (muñeca Lele) was born in the Magic Town of Amealco, a municipality located in Querétaro State (one of the 32 federal entities of Mexico), by a group of artisans from the communities of Santiago de Mexquititlán and San Ildefonso Tultepec, who have passed this artisan tradition from generation to generation.

Lele in Otomí (the language of an indigenous people of Mexico, with the same name, inhabiting the central Mexican Plateau region) means baby. Therefore that is its true meaning: baby doll. Among its characteristic features are the long braids, with crowns and ties of cheerful colors, as well as its traditional dress, since this represents the clothing of its creators. Due to its importance, the Otomí doll was named Cultural Heritage of Querétaro on April 18, 2018. In addition, it has its museum located in its town of origin.

A tradition inherited from generation to generation is now the livelihood of dozens of families. Its manufacture is one hundred percent handmade and has become almost a ritual. The braids and crowns woven with brightly colored bows identify the Lele anywhere in the world.

Lele doll has become so popular that she toured the world in 2019 with a giant doll. She has been to faraway places like UK, China, and Australia.

Baños, Servicios, Sanitarios

Public toilets in Mexico are omnipresent. There is no way not to be able to find one when you need it. They are located everywhere, in parks, in streets, and shops. They are a business rather than a facility. Many shops advertise in big letters that they have toilet facilities. As it is a business, their use comes with a price: it costs between 5 and 8 pesos. You have to look for one of the signs:

baños, Servicios, or Sanitarios.

Advertising WC facilities in Cholula, with the help of Frida Kahlo.

Pre-Columbian civilizations

The Pre-Columbian civilizations of the Mayas, the Olmecs, the Incas, and the Mexica (Aztecs) are some of the most significant ancient cultures. They are very often lumped together or confused, although entirely distinct.

The Mayas were the first and settled in Mexico and Central America. Next came the Olmecs in Mexico. They were followed by the Inca, located in modern-day Peru—finally, the Mexica, who settled in Mexico. Although the Mayas were present in Mexico before the Olmecs, the Olmecs established and built their civilization before the Maya people unified to build theirs.

Maya relief from Tonina, depicting a captive slave.

The Mayan civilization started in 2600 bc and built most of their great cities from AD 250 to AD 900. The Mayas were not wiped out like some other cultures but gradually dissipated. The various Mayan kingdoms withstood defeat at the hands of the Spaniards for almost two centuries! The Mayans left a prosperous legacy encompassing parts of Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

The name, Olmec, is derived from Mexica writings. The Olmec established themselves around 1600 bce and lasted about 1,000 years. They wrote in hieroglyphics, as did most of the cultures that followed them. They never built any major cities but built one pyramid before gradually disappearing. Their most famous legacy is the mystery of the Olmec heads: 9 ft. Tall heads made of stone.

The Inca can be traced back to about AD 1200, living in the mountains of present-day Peru. They were highly advanced and had an army, laws, roads, bridges, tunnels, and a complicated irrigation system. A civil war broke out, weakening the empire and quickly causing defeat by the Spanish invaders.

The Mexica (the Aztecs) built Tenochtitlan in AD 1325, meaning they were much younger than the other three civilizations. The Mexica founded their mighty city on Lake Texcoco. The Mexica gradually conquered the rest of the area until they fell at the hands of the Spanish invaders in 1521.

Though the cultures are alike in many ways, like their building of pyramids, and the use of hieroglyphics (except the Inca), they are four distinct cultures that rose and fell at different times, not all for the same reasons.

The Sinking City

For over 100 years, it has been known that Mexico City has been sinking due to the removal of water from the ground it's built on. This sinking has reached an alarming rate of 50 centimeters per year, and a new study suggests there is no hope of reversing it.

Mexico City is built over the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan and Lake Texcoco, a system of salt and freshwater lakes. The Aztecs had dikes to separate the fresh water and stop floods, but those were destroyed during the Spanish colonial invasion and city siege in the 1500s. Afterward, the Spanish drained the lake with only a small section remaining.

In the 1900s, the city sank at 9 centimeters a year. Since the late 1950s, when that rose to 29 centimeters a year, the amount of water that could be drilled from the ground in the area was capped. While that helped slow the sinking, it did not stop or reverse the process. For a while, it went back to 9 centimeters, but in the last two decades, it rose to a sinking rate of 50 centimeters in some parts of the city. Now, scientists believe that the amount of water removed no longer affects the level of subsidence, which is almost entirely irreversible. So far, the clay layers below the city have been compressed by 17 percent and are unlikely to bounce back. The compression of these layers continues; the whole layer will end up compressed by 30 percent, which could lead to additional subsidence of up to 30 meters in 150 years.

With a population of over 21 million people, Greater Mexico City is the eleventh-largest metropolitan area in the world and the largest in North America. Over 70 percent of its drinking water comes from groundwater extraction wells throughout the basin.

The city's sinking is apparent in the buildings around Plaza Mariana at the Basilica de Guadalupe in Mexico City.

Carbadge treatment

When I first saw the garbage trucks collecting in Mexico City, I was impressed because they circulated throughout the day and not at night, as is usually the case in other big cities. Second, the sanitation workers sorted and separated the garbage on the spot. I thought the garbage collection service had a sophisticated system where the employees did all the on-site recycling work.

But this is not the case. The people on the trucks are not city employees but civilians who voluntarily collect and separate the garbage to sell recycled material, like paper or plastic. Thousands of waste-pickers, known as “pepenadores” (pickers or scavengers), make a living from picking through the waste in the city. The “official” system relies on some 10,000 “volunteers” who receive tips from people to take their garbage away and sell the recyclables they pick out of the waste.

Police

After returning from Mexico, I watched a recent Mexican documentary about the police in Mexico City. Low wages and poor education result in an incompetent body and widespread corruption. You will tell me none of this is unheard of since the police in most if not all, countries are corrupt.

The point is that economic inequality in Mexico is extreme, and corruption at all levels of social and political life is very evident. Local governments are also the most corrupt, entirely controlling the police hierarchy in their areas. This results in using the police as an integral part of organized crime, often led by locally elected lords. In Mexico, there are estimated to be over 110 thousand missing citizens. The police do nothing to help find their tracks because, in most cases, they helped organized crime to make them disappear. All this happens with the tolerance or even the mandate of the local rulers and governments of the country.

In the city, the police presence is heavy, although I don't know how effective all those men and women dressed in black, armed, and wearing bulletproof vests are! The most "impressive" thing, however, is that the police patrols use black pickup vans, in the back of which stand police officers with automatic weapons.

This system, though, has lots of problems, and Mexico City's Commission on Human Rights (CDHDF) has issued recommendations on waste management services to address the labor conditions of the city's waste pickers. It includes measures that the central government and the delegations (municipalities) should implement to guarantee the labor rights of waste pickers who provide the services of collecting, sorting, and transporting recyclable materials at no cost to the city. The recommendation also calls attention to the need to design a social security scheme for waste pickers; prevent work-related diseases; provide adequate equipment and work facilities; and, given the particular vulnerability of these workers, grant special state protection.

La masacre de Ayotzinapa

On September 26, 2014, forty-three male students disappeared from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College after being forcibly abducted in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico. They were allegedly taken into custody by local police officers from Iguala and Cocula in collusion with organized crime. The mass kidnapping has caused continued international protests and social unrest, leading to the resignation of Guerrero Governor Ángel Aguirre Rivero in the face of statewide protests on October 23, 2014.

Portraits of the 43 students disappeared in "La masacre de Ayotzinapa". Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City.

The students had annually commandeered several buses to travel to Mexico City to commemorate the anniversary of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre; police attempted to intercept several buses by using roadblocks and firing weapons. Details remain unclear on what happened during and after the roadblock. Still, the government investigation concluded that 43 students were taken into custody, handed over to the local Guerreros Unidos ("United Warriors") drug cartel, and probably killed. This official version from the Mexican government is disputed. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) assembled a panel of experts who conducted a six-month investigation in 2015. They stated that the government's claim that the students were killed in a garbage dump because they were mistaken for drug gang members was "scientifically impossible".

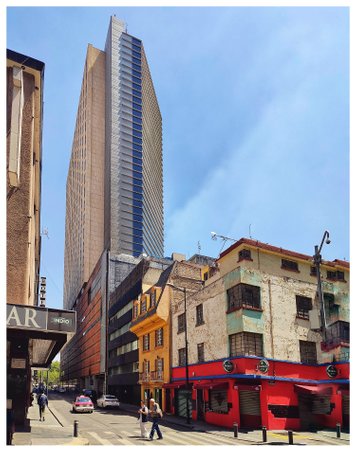

Architecture

Mexico City is vibrant, energized, and fast-paced. Even the food, full of flavor, seemingly tells a story about the past, present, and future of the city and its people. But nothing tells us more about the history of Mexico City than its architectural evolution. From the first day, the visitor is impressed by the city's architectural wealth and centuries of history left intact marks in the city.

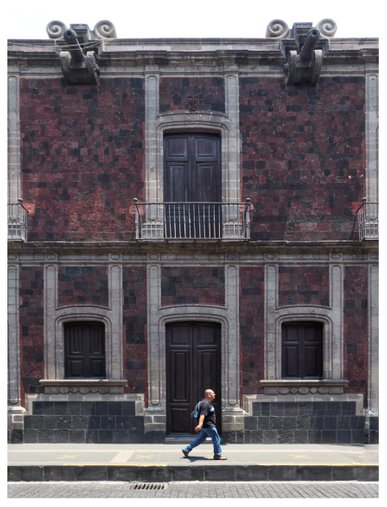

Colonial Architecture in the city center (notice the black and deep red volcanic stone used).

Take a walk through the green Viveros de Coyoacan, and arrive at the Frida Kahlo Museum, a cobalt blue compound and the former home of the artist and her husband, Diego Rivera. The museum, which houses work by both artists and their personal belongings, immediately jolts you into the world of Mexico’s most famous artistic duo. If you want more of Diego, head to his Studio-Museum, Anahuacalli; the “pyramid” -known to many- is a construction of the 20th century inspired by pre-Hispanic architecture, the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, and functionalist aesthetics. It was raised in stone to house the creations of ancient civilizations.

Coyoacan architecture: Alcaldía Coyoacán (left), Frida Kahlo Museum (center) and Diego Rvera Studio-Museum, Anahuacalli.

For more 20th-century Mexican architecture, visit the Casa Luis Barragan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and perhaps the most Instagrammable location ever with its bright-pink courtyard and minimalist design. A few blocks over, ring the bell to the Kurimanzutto Gallery and enter the modern concrete and wood space.

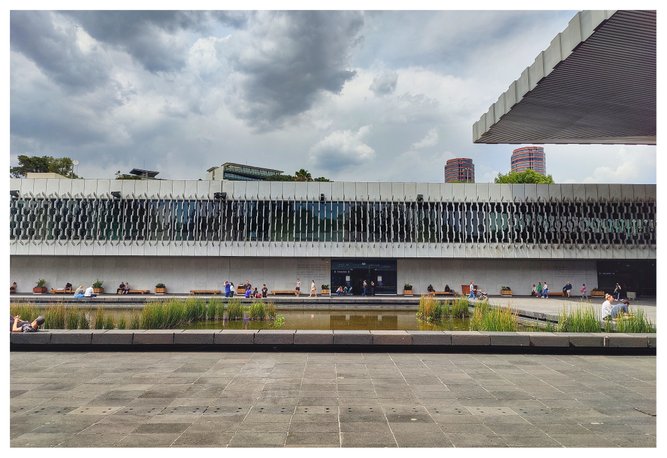

Travel an hour outside the city to the pre-hispanic city of Teotihuacan, where you can climb to the top of the pyramids and experience Mexico from new heights. Upon your return, visit the architecturally distinct National Museum of Anthropology and the Museo Rufino Tamayo, the city’s contemporary art museum. Together they will contextualize your architectural and cultural journey through Mexico City, ultimately a celebration of culture and authenticity.

The pre-hispanic city of Teotihuacan (left) and National Museum of Anthropology (right)

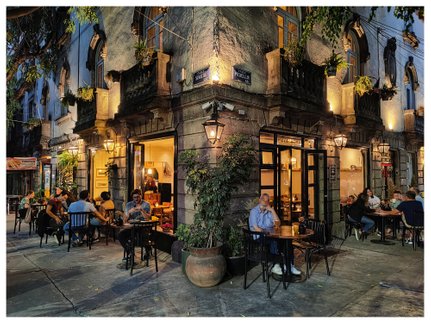

Big projects, like museums, office buildings, churches, stadiums, public libraries, and other university builds, impress the visitor. Still, for me, nothing is more impressive and decisive for the visitor's love for this city than the abundance of smaller residential buildings in the neighborhoods of Mexico City. Urban houses of the late 19th or early 20th centuries, bigger or smaller, richer or humbler, painted in vivid colors, are the pleasure of Mexico City. Cool, shaded roads like Colima Street in Roma Norte have a retro look that floods your senses with beauty and nostalgia. Combine this with the black-red robustness of the colonial era buildings in the center of the city (made of black and deep red volcanic stone, which is abundant in around Mexico City), and you have the perfect picture of a city like no other.

The richness of the Mexican City architecture.

Catholicism

I don't know how to describe it, but while in Mexico, I thought this was the most "Catholic" country I have visited. Mexico appears to the visitor to be more Catholic than Italy or Spain, for example. The churches are scattered with colorful statues of dubious artistic aesthetics but of great religious value. Statues of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and the saints wear colorful dresses, have human hair, and wait for the flock in every corner of the church. Stalls inside and outside the churchyards sell figurines of all the saints, amulets, and rosaries. In general, an atmosphere of "holiness" and Catholicism is forced upon you.

In churches and monasteries, you get the impression that the Inquisitor will appear to punish you, even though the country has taken very early steps to limit the church's power and its involvement in secular power.

"EL SEÑOR DEL REBOZO" (Convent of Santo Domingo de Guzman)

The Virgin of Guadeloupe souvenir doll (left), a madona "altar" in a park at Colima street, Roma Norte (center), a overdecorated altar in a Puebla church (right).

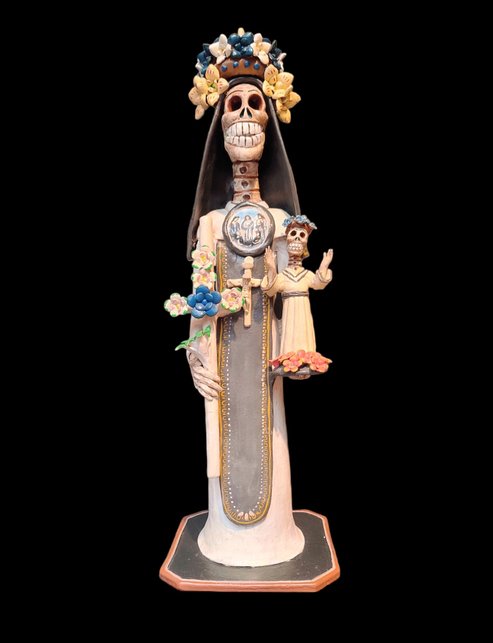

On the other hand, pre-Columbian religious habits and superstitions are well preserved in the country. Magic and witchcraft reign, and new "religions," such as the worship of "Santa Muerte", are constantly increasing their influence on people, especially in the lower educational and economic strata. Palmistry, tarot, and purification from evil spirits are standard practices.

You have to visit the area next to the archeological site of the Templo Mayor and the Cathedral to see various "wizards" dressed in costumes and giant feathers reminiscent of Indian ancestors exorcising evil with herbs and incense.

Santa Muerte.

Magicians outside the Mexico City Cathedral (Zocalo).

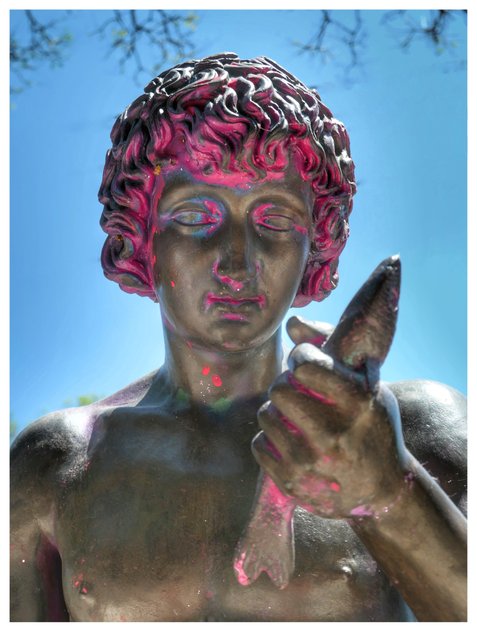

Monuments and statues

Mexicans are obsessed with statues and monuments. There are countless statues in Mexico City to the point of exaggeration. Parks and streets are dotted with small, large, and colossal statues. Many statues are exact copies of famous European ones, like Michelangelo's David (Plaza Río de Janeiro), or even whole monuments are exact copies, like Fuente de Cibeles(Plaza Villa de Madrid).

Even the city's symbol is a statue: Ángel de la Independencia. The city's main avenue, Paseo de la Reforma, has a statue every few meters along its entire length.

The Ángel de la Independencia (Paseo de la Reforma)

A copy of Michelangelo's David (Plaza Río de Janeiro)

The Ángel de la Independencia (Paseo dela Reforma)

Torre Cabalito (Paseo de la Reforma)

One of the many statues in the Avenida Juarez (in front of Alameda Central).

Monument to Cuauhtémoc (Paseo de la Reforma).

Sculpture made out of guns stands outside the Museo Memoria Y Tolerancia in Mexico City.

Altar a la Patria at Bosque de Chapultepec.

Food

Before going to Mexico, I read about how good Mexican food is everywhere. They say Mexican food is in the top 5 national cuisines. The truth is that my experience with Mexican food in Europe and America is good. I never said wow, what a burrito, or What a delicious taco, but yes, all these can be tasty. I believed that if I went to Mexico, the food would be better than the one I am used to.

Alas! First, let's clarify that the Mexican food we know in the West is not precisely Mexican but American (Tex-Mex). And also, the taste is very subjective, and some will disagree with my writing here. The taste is very personal indeed, but I consider myself very open-minded when it comes to food, and I am also adventurous when it comes to taste.

Well, when I tried the authentic food, it was a disappointment. A disappointment. Many ingredients are thrown onto a plate, and on top of them, different sauces. The sauces soak the rest of the ingredients, disappointing the whole plate. This is what I call the food of the lousy housewife! I tried the food in various good restaurants and street canteens (this involves the risk of stomach disorders and needs special attention), but no!

The good news is that Mexico City is a megapolis where you can find the food you want in excellent quality. So, you can survive with Chinese, Japanese, American, and Italian food! Additionally, there are a lot of cafes in the city that serve light meals, brunch, and breakfast, which is very good. Thus, if not very Mexican, one can survive on delicious eggs or omelets! Huevos Rancheros (Ranch Eggs) is the most popular Mexican breakfast with eggs.

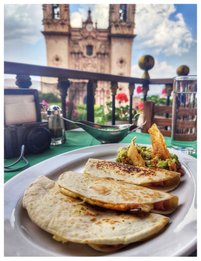

The iconic tacos! Here served at "Casa de los Azulejos" (Sanborns restaurant).

Tacos de cochinita pibil. "Casa de los Azulejos" (Sanborns restaurant).

For example, the best restaurant for me in the city, where I often ate, was an Italian with great American-style pizzas.

Another disappointment of the city's gastronomic scene is bread and cakes. Mexicans need to learn what bread is! They may know about tortillas, but no bread. Their bread is a kind of soft, tasteless, white bread with a touch of sugar ... or a lot of sugar! Cakes are primarily tasteless, unappealing, and it is obvious that "nouveau patisserie" never made it to Mexico. Croissants are very popular but are not fluffy, do not smell butter, and tend to be flat.

"Pizza Roma" in Roma Norte is my favorite restaurant of the City (Medellin & Colima).

Cafes, are evereywhere in the city. The server simpler dishes, but their quailty in general is very good. Cheese tost (left, omelets (center), french toast (right).

Shrimp tacos, machaca, Quesadilla, mole.

Al pastor

Al pastor (from Spanish, "shepherd style"), tacos al pastor, or tacos de trompo is a preparation of spit-grilled pork slices originating in the Central Mexican region of Puebla and Mexico City, although today it is a standard menu item found in taquerías throughout Mexico. The method of preparing and cooking al pastor is based on the lamb shawarma brought by Lebanese immigrants to the region. Al pastor's flavor palate uses traditional Mexican adobada (marinade). It is a popular street food that has spread even to the United States. In some places taco al pastor is known as taco de trompo or taco de adobada. A similar dish also from Puebla that uses a combination of middle eastern spices and indigenous central Mexican ingredients is called tacos árabes.

During the 19th century, variations of a vertically grilled meat dish, now known by several names, started to spread throughout the Ottoman Empire. The Lebanese version, shawarma, was brought to Mexico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by a wave of Lebanese immigrants, mainly Christians such as the Maronites, who have no religious dietary restrictions on eating pork.

In the 1920s, in Puebla, lamb meat was replaced by pork. Mexican-born progeny of Lebanese immigrants began opening their various restaurants. Later, in Mexico City, they began to marinate with adobo, and use corn tortillas, which resulted in the al pastor taco. It is unknown when they began to be prepared as we know it today. However, some agree that it was in the 1960s when they became famous.

The streets in Mexico are dotted with small cantinas and kiosks offering food. The heart of food beats in the streets.

The quality of the coffee in Mexico City is excellent, and the visitor has all the choices he has in any big city today: espresso, cappuccino, americano, etc. Besides the standard brands, there are also roasters here that serve good quality coffee from small producers. Remember that Mexico is a significant producer of unique varieties of coffee.

Starbucks is very popular in Mexico, and the stores serve the well-known varieties of coffee found all over the planet, but also some Mexican varieties. Starbucks is being competed by a Mexican company, Tierra Garat. Tierra Garat uses only Mexican coffee beans (from the best regions of the country -Chiapas, Veracruz, and Oaxaca) in a rustic setting.

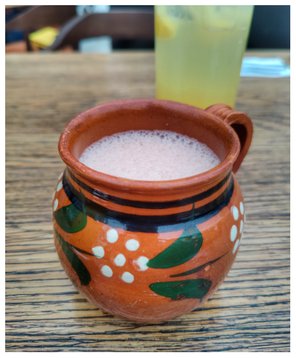

Chocolate is invented in Mexico. It was known as the "food of the gods" and even used as currency by the Aztecs. The nobles had been drinking chocolate for centuries before the Spaniards arrived here.

The craft of chocolate making can be traced back to 1900 BCE in Mesoamerica, and the way the Aztecs prepared it is similar to how Mexicans do today. The cacao beans are typically roasted, peeled, and then ground into a paste using acetate, a traditional tool for hand-grinding materials, or Molino, a mill. Sugar is then mixed in, and cinnamon is traditionally added.

That said, chocolate making in Mexico has evolved over the years, and regional differences do appear. In some regions of Oaxaca, Mexico, the cacao bean shell is left on, resulting in a more bitter flavor. As the birthplace of chiles, Mexican chocolate also often features chile varieties like guajillo, pasilla, and habanero, which are typically finely ground and blended in. When the Spanish arrived, they brought certain ingredients, like nuts and spices. The common practice of adding almonds and cardamom to Mexican chocolate stems from this.

Finally, the chocolate is worked into its final shape, which is often a disc or log. This rustic presentation works perfectly since Mexican chocolate is still handmade in many regions.

Just dissolve a chocolate disk into hot milk to prepare a chocolate drink.

Tierra Garatt coffee cup.

Matcha latte is popular in upscale areas like Condesa and Roma Norte.

Hot mexican chocolate drink.

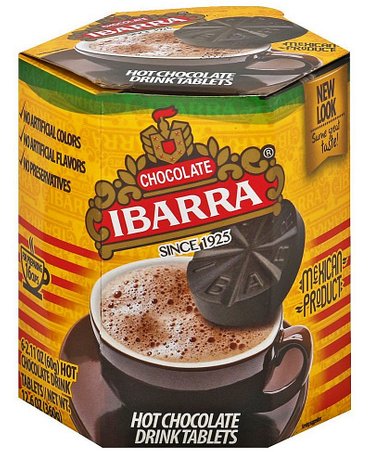

Ibarra

One of the most traditional Mexican chocolate brands, Ibarra is famous for so-called “table chocolate”, used to make the iconic hot chocolate that Mexicans love.

Ibarra is about 30 years older than the factory that currently makes it, Chocolatera de Jalisco. The company, established in 1954, hails from the western state of Jalisco, aka the informal capital of Mexican chocolate.

These all-time classics are the go-to chocolate discs of Mexican-style hot chocolate. While you can eat them raw if you want, their rough texture makes them better suited to be melted instead.

Each disc comprises eight segments that you can use to measure the amount of chocolate you’ll be adding to your beverage. One disc typically yields four cups, depending on how strong you want your hot chocolate.

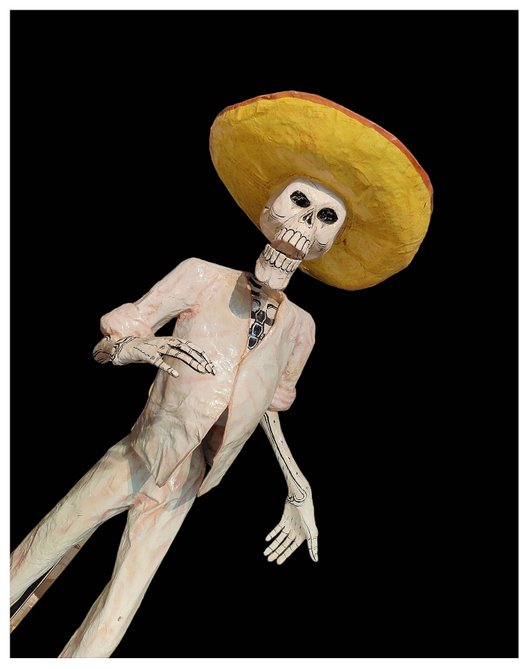

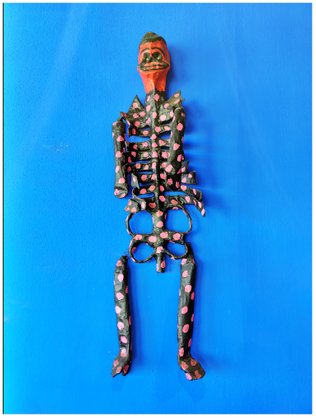

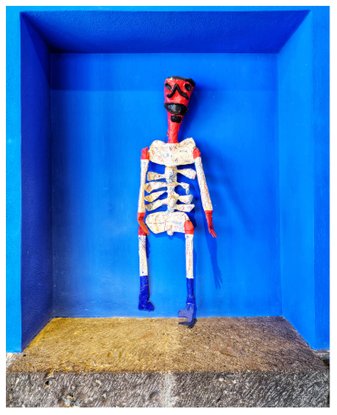

Calaveras y calacas

In most cultures, bones (especially the human ones) conjure up fear and are used to scare children, and no good Christian-minded soul wants to be reminded of death. Then, here we come to Mexico and find skeleton figures in all the art and artisanal shops. There's even a children's cartoon named "Huesita" or "Little Bone". Welcome to Mexico.

The answer to why Mexicans have such "affection" for skulls (calaveras*) and, to a lesser extent, skeletons (calacas) are complicated, as different cultures tend to be, and Mexico's culture is complicated. The Spanish conquered the indigenous people of Mexico half a millennium ago. Even though most indigenous peoples were killed or devastated by unknown European diseases, many who survived the Spanish brutality were put to work. Over the centuries, the cultures of conquerors and conquered have melded in fascinating ways.

(*) the term is often applied to edible or decorative skulls made (usually by hand) from either sugar (called Alfeñiques) or clay used in Mexican celebrations such as the Day of the Dead. Calavera can also refer to any artistic representations of skulls.

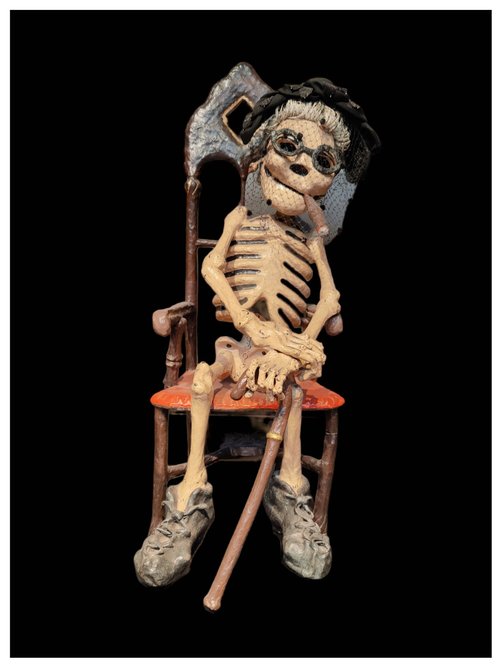

Museo de Arte Popular. "Santa muerte".

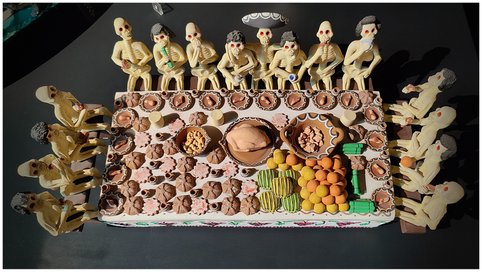

One of these ways is the celebration of "Día de Los Muertos", a two-day festival honoring the ancestors (November 1st and 2nd). The skulls are often adorned with colorful flowers, butterflies, and other patterns. On the other hand, the skeletons are often depicted dressed in traditional Mexican clothing or modern garb. Every year the departed visit, feast, and party with the living. The next day all go to the cemetery, where the party continues into the night. Then the living goes home, and the dead await the following year. Though the Catholic church was able to move the date of this celebration to coincide with All Saints Day and All Souls Day, this is where Christian influence mostly stops. The Day of the Dead can seem unsettling at first glance, but it is a celebration of the cycle of life and not as depressing as the name might suggest. Given the importance of the Day of the Dead in Mexican culture, UNESCO declared it to be an intangible cultural heritage to preserve the festivities (UNESCO, 2008).

Popular art. (Museo de Arte Popular).

It's good to remember that most of Mesoamerica's cultures were interrelated. The same ball courts can be found in ruins near Phoenix as on the Yucatan peninsula. They also shared their religions. An integral part of that religion was the depiction of many gods as skeletons. Skeletons were considered good luck and symbolized fertility, the dichotomy of life. Quetzalcoatl was said to have stolen bones from the god of the underworld to create the different races of humanity. It was believed that the god Mictlantecuhtli and his wife presided over the world of the dead. They are always portrayed as skeletons.

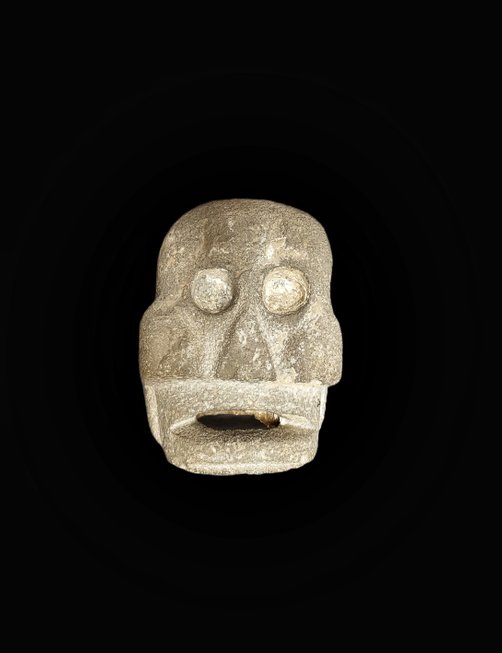

Museo Nacional de Antropología. The Aztec goddess Mictecacihuatl (left). A stone skull (right).

Skulls and skeletons are often present in altars that families construct to honor their dead loved ones, who are invited to come back from the underworld to the land of the living to celebrate with the family, eat their favorite dishes and even drink their favorite beverages. Altars are a mixture of pre-Hispanic and modern Mexican cultures and often feature pre-Hispanic foods such as mole sauce and mezcal. Skeletons are even present in the food; there is a type of bread called the 'pan de Muertos' or bread of the dead, with decorations in the shape of bones on top of it. Skulls are a part of the altars in the form of sugar skulls. These are decorated with colorful sugar paste, and a person's name can also be added to the forehead. Skulls can also be made of chocolate, a popular alternative offering assorted flavors besides plain sugar.

An altar presenting skulls.

Skulls and skeletons are also important aesthetically. Great care is put into every piece to make them as beautiful as possible, a concept that might seem contradictory initially, given that these representations of death. In Mexican culture, however, there is a belief that beauty can be found even in death, even when the outward signs of beauty are gone.

The depiction of death as a colorful entity developed as a mixture of Indigenous beliefs from before the Spanish conquest and Catholic beliefs from after the conquest. This celebration has "pre-Hispanic Aztec rituals tied to the goddess Mictecacihuatl, the Lady of the Dead, who allowed spirits to travel back to earth to commune with family members". Altars are often decorated with cempasúchil flowers, and the vibrant yellow of their petals is often reflected in the yellow decorations on the sugar skulls. Sometimes the same color is used in the clothing of the skeletons placed on the altars. The same is true for skeletons, as many techniques are used to make them, though they are not usually edible even when placed in altars. While the skulls are often made of comestible ingredients, they can also be made of paper-mâché, ceramic, and cardboard.

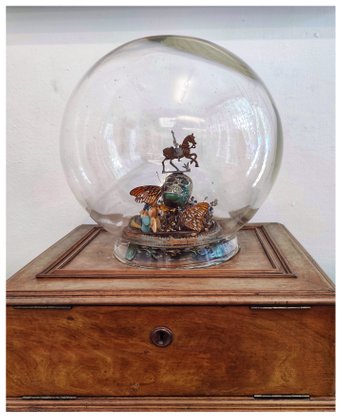

Frida Kahlo's skeleton artifacts (left/right). A crystal ball containing a skull decorated with butterflies, etc. (middle). Museo Frida Kahlo.

One of the most famous depictions of a skeleton in Mexican culture is José Guadalupe Posada's "Catrina", an illustration of a skeleton wearing a Victorian, wide-brimmed hat with feathers. Posada described this illustration as a" 'democratic death' given that death will eventually find everyone, rich or poor, white, or not, in the end, everyone will become a skeleton". The name Catrina is the feminine version of the word Catrin, which was used to denote a man dressed elegantly, and in fact, the male version of the Catrina is known as a Catrin, with Catrines and Catrinas as the plural forms. Sometime later, in 1947, Diego Rivera included the Catrina in a mural titled "Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central" (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Central Promenade) in which the Catrina is seen wearing a feathered serpent around her neck. The feathered serpent is an allusion to the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, the creator god that brought wind and rain and is known as Kukulkan in the Mayan tradition.

A detail of Diego Rivera's mural "Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central" depicted Catrina.

Multicolored Calaveras made of papier-mâché.

Poetry written for the Day of the Dead is known as "literary Calaveras" (calaveritas literarias) and is intended to criticize the living while reminding them of their mortality humorously. These short, often satirical, texts poke fun at difficult situations and remind the reader that death comes for everyone in the end, and there is no escape. Literary Calaveras appeared during the second half of the 19th century when drawings critical of influential politicians began to be published in the press. Living personalities were depicted as skeletons exhibiting recognizable traits, making them easily identifiable. Additionally, drawings of dead personalities often contained text elements providing details of the deaths of various individuals. Calaveritas literarias continue to be popular even today.

Sometimes known as "sugar skull make-up" or "Catrina make-up, " face-painting like a skull with ornate elements is popular in Day of the Dead celebrations.

Modernity continuously attempts to push any thoughts of death out of the mind, as though the mere mention of it was enough to turn an otherwise happy day into a gloomy one. Skulls and skeletons in Mexican culture are in direct opposition to that erasure of death in everyday life as they are gentle reminders that life is temporary and only death is inevitable. Their importance lies in those reminders and their silent encouragements to spend more time enjoying life, trying new things, and finding new experiences. They also offer comfort after death by highlighting the bond between life and death and conveying that death is not the end of a relationship but rather an opportunity for new and exciting celebrations.

Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares (Coyoacán).

Contemporary Falk art (Museo de Arte Popular).

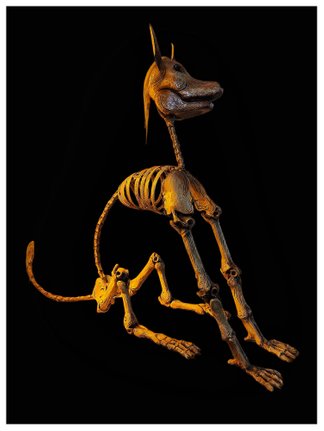

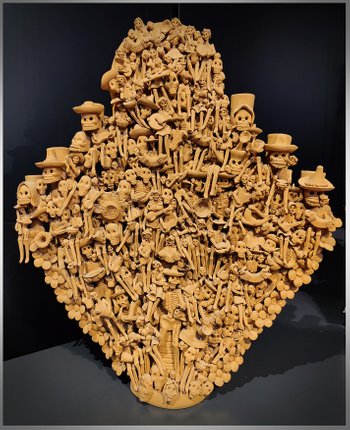

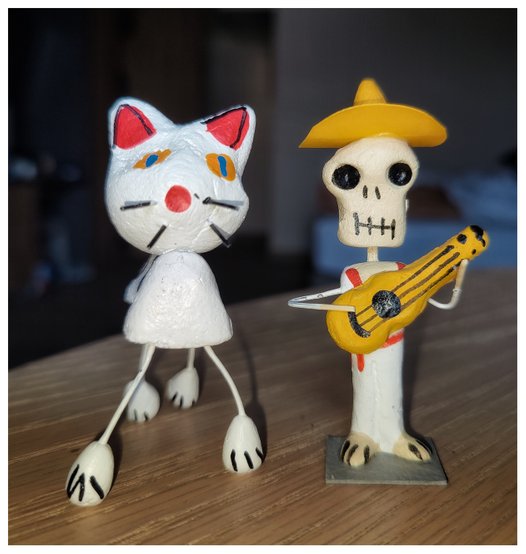

Contemporary Falk art (Museo de Arte Popular). A Catrina-like figurine made of sugar (left), a dog skeleton made of wood (middle), and a "tree of life" made of clay (right).

Calacas are prominently featured as representations of the deceased in "The Book of Life" and "Coco" animated films.

Calaca-like figures can be seen in the Tim Burton film "Corpse Bride", Neil Gaiman's movie "Coraline", video games such as "Little Big Planet" and "Guacamelee", and the 1998 Tim Schafer computer game "Grim Fandango".

In "Monster High', Skelita Calaveras is a calaca and is the daughter of Los Esklitos (The Skeletons).

In "El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera", the villain Sartana of the Dead is a calaca and commands various calacas in her service.

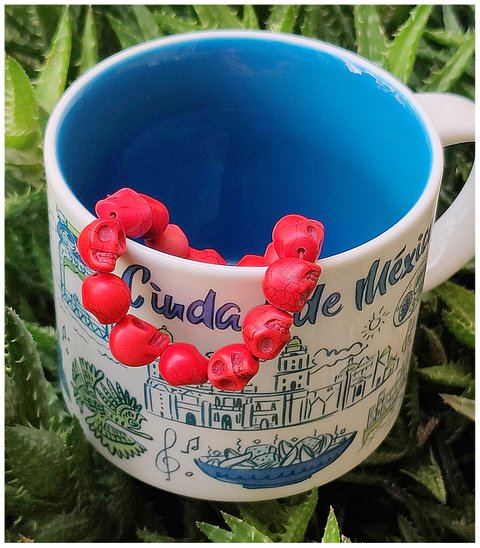

Souvenirs I brought back from Mexico.

Today, as tourism is flourishing and TV and Cinema bring all cultures into our living rooms, the Mexican skulls intrigue everyone and "press" local artists to take all these to further horizons. The results are sometimes exciting and sometimes tacky. One is for sure; though, there is no way to visit Mexico and not bring back home skeletons of all sizes and materials to friends. One out of two souvenirs are depicted skeletons.

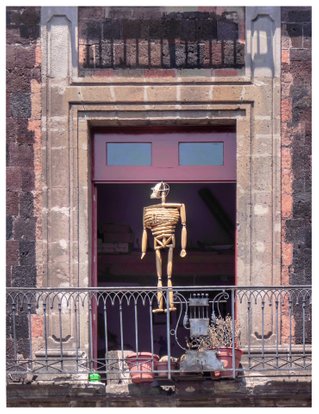

Window decoration in Centro.

A shop decoration next to Kahlo's museum.

Árbol de la Vida

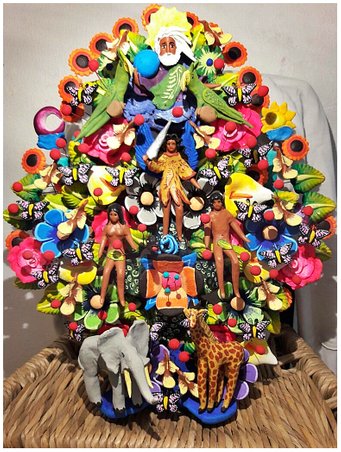

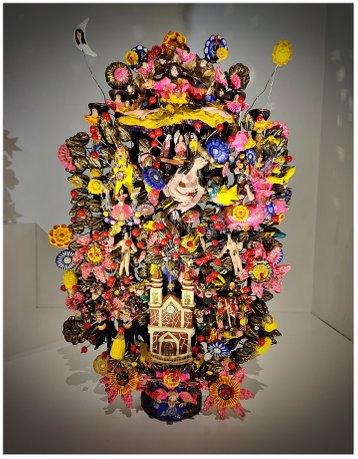

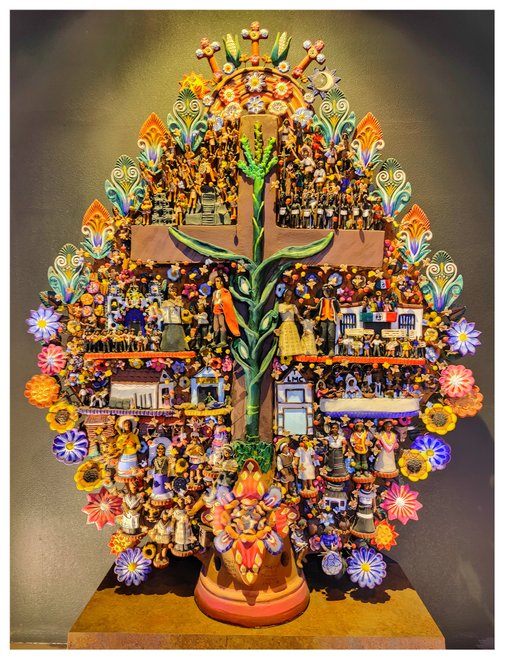

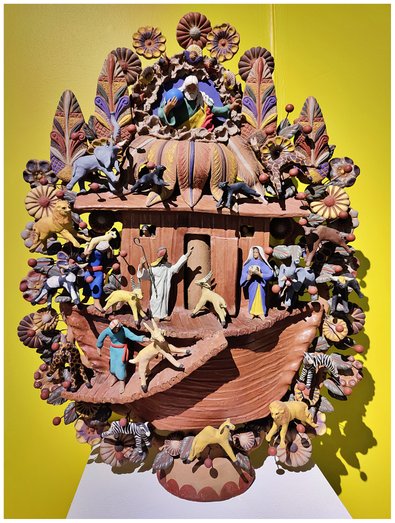

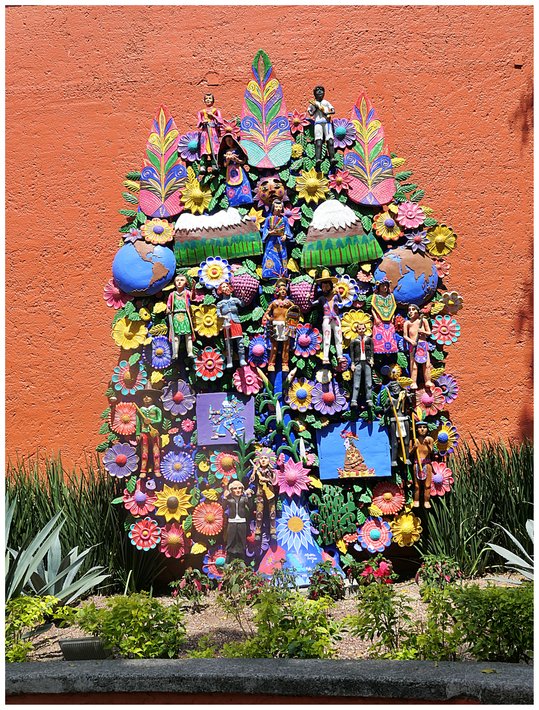

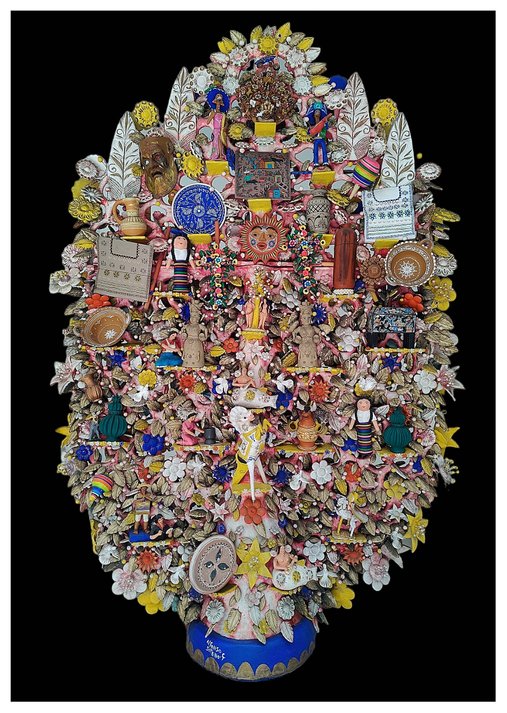

When visiting Mexico, there is no way not to be hit by strange and complicated pottery sculptures in a museum or a souvenir shop called 'Trees of Life' (Árboles de la Vida). These sculptures are pottery traditional in central Mexico, especially in the State of Mexico. The tree is assembled while soft unfired clay from many pieces is formed separately. The fashioning of the trees in a terracotta sculpture began in Izúcar de Matamoros (Puebla State). Still, today the craft is most closely identified with Metepec (Mexico State), which distinguished its trees by painting them in bright colors. The tree sculptures have become emblematic of this municipality and are part of a clay sculpture tradition found only here. Traditionally, these sculptures are supposed to consist of specific biblical images, such as Adam and Eve or the Noe's Arc. Still, recently, trees have been created with themes utterly unrelated to the Bible.

A Tree of life at Museo de Arte Popular.

The creation of Trees of Life is part of the pottery and ceramic traditions of the central highlands of Mexico. Pottery in this area can be traced back to between 1800 and 1300 B.C., including clay figures. The painting of these figures begins later after Olmec's influence arrived in the area. Around 800 A.D., Teotihuacan influence brought religious symbolism to many ceramic wares. From then on, Matlatzinca pottery in Mexico State continued to develop with multiple influences since it was strategically positioned between the Valley of Mexico and the states of Morelos and Guerrero.

After the Spanish conquest, friars destroyed articles, including ceramics, that depicted the old gods and replaced them with images of saints and other Christian iconography. The depiction of a "tree of life" in paintings and other mediums was introduced to evangelize Biblical stories to the native population.

A Tree of life at Museo de Arte Popular.

The most traditional of the trees of life, that of the world's creation contains several vital images. At the top of the sculpture, an image of God is placed. Underneath are images of the world's creation in seven days, such as the sun and moon, the animals, and Adam and Eve. The serpent from the Biblical story also appears, as does the Archangel Gabriel at the bottom, who casts out Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. Overall, the tree sculpture looks something like a candelabra. The trees are made primarily for religious and decorative use. Those that contain incense burners are more likely to be used religiously. In Izucar de Matamoros, these trees appear in processions such as those for Corpus Christi.

During most of the colonial period, ceramics in Mexico State were mainly produced for self-consumption. Ceramics became a fusion of Spanish and indigenous techniques and designs. It remained so until the first half of the 20th century when decorative and even luxurious pieces began to be produced. The Tree of Life typifies this type of work, especially those that are not religious in function. These non-religious trees have themes such as death or spring.

A Tree of life at Museo de Arte Popular.

The trees are made from clay fired in gas ovens at a low temperature. Most trees are between 26 and 60 cm tall and can take anywhere from two weeks to three months to create. Huge pieces can take up to three years. These trees vary in size from miniatures to gigantic public sculptures. Variations in the craft have appeared in recent decades. Most trees are created and sold by artisans who have learned how to make them from their parents and grandparents.

Many trees have unique themes today, but the most common is the duality of life and death and man's relationship with the natural world. Many of these represent the history of a famous person or place and are custom ordered, as the trees of life have become famous objects of art worldwide by well-known Mexican artists. However, purists insist that those that do not relate to the Garden of Eden are not actual Trees of Life.

A Tree of Life at Museo de Arte Popular, depicting Noe's Arc.

A big Tree of Life in the courtyard of Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares (Coyoacán).

A big Tree of life at the patio of Museo de Arte Popular.

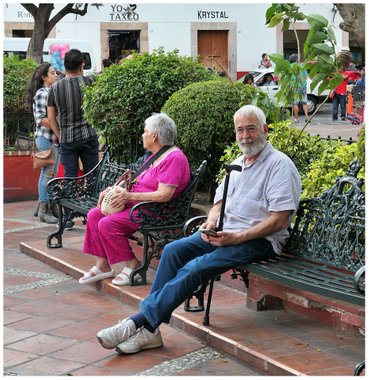

Cast iron benches

Another tremendous Mexican urban culture item is the iron-made public benches. These benches are not made of perishable materials such as wood, stone, or concrete but cast iron. They are exquisite and elaborate and usually have the emblem of the Municipality they are placed on.